Pilots, generally speaking, like to share stories of past adventures. No doubt we’ve all heard someone say, ‘Back in my day…” Well that got us thinking about flying before everyone had a GPS or an iPad in the cockpit, and what lessons could be learned from old-time aviators. One way to do that is talk to members in your club who have a lot of flying experience to learn what they have picked up over the years.

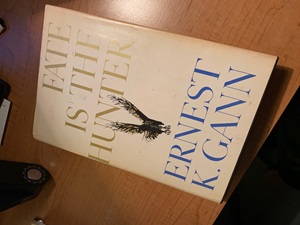

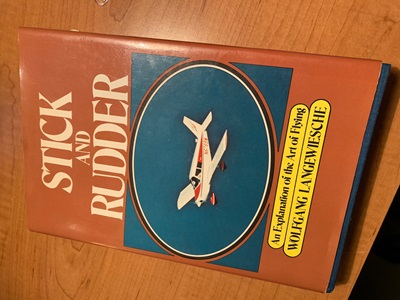

Another resource is picking up a classic aviation book, such as Fate is the Hunter by Earnest Gann or Stick and Rudder by Wolfgang Langewiesche. So, that is what we did. As we turned the pages of these seemingly ancient texts, they brought back memories of lessons we learned from old-time instructors during our flight training, as well as a few old tricks that were new to us. Here are a few things that stuck out from what we’ve read.

Fate is the Hunter

Fate is the Hunter, considered by many to be the greatest aviation book ever written, is Gann’s memoir of being a pilot in the early days of the airline industry in America. Published in 1961, Gann details his growth from a young barnstormer going through airline ground school in the 1930s, serving an apprenticeship as a co-pilot on DC-2s and DC-3s, to becoming a captain. His journey takes him literally around the world—from Route AM-21 between Newark, New Jersey and Cleveland, Ohio, to flying DC-4s and C-87s, the cargo version of the B-24 bomber, across the North Atlantic as a civilian pilot with the Air Transport Command in WWII. He flew similar aircraft over the Hump between India and China, as well as Lockheed Lodestars in South America at a time when navigation aids, radio stations and maintenance facilities were unreliable. The book concludes with his post-war transoceanic flights from California to Hawaii and then on to Asia in the last of the great four-engine piston airliners before the dawn of the jet age.

His writing picks up where Antoine de Saint Exuperary leaves off in his novels and autobiographical works about pioneering airmail routes from France to North Africa and across the Atlantic in open cockpit biplanes in the 1920s. Although the accounts are real, Fate is the Hunter reads like a novel and two stories in the book were the basis for novels Gann wrote that were turned into films starring John Wayne.

The first, The High and the Mighty, is about an Air Transport Command aircraft that makes an emergency landing in the remote Canadian wilderness in winter and the effort to rescue the crew. In real life, Gann was supposed to command the ill-fated flight and was bumped because of seniority. He was one of the pilots that searched for the downed plane.

The second novel, Island in the Sky, is about a DC-4 flight from Hawaii to San Francisco that experiences an engine failure at night after reaching the point of no return. The movie is considered the first aviation disaster film, and it inspired the Airport movies of the 1970s. Amazingly, the true story is more dramatic than the fictionalized account.

I found Fate is the Hunter a fascinating window into an era before automation was common and pilots and navigators relied on their airmanship and pilotage skills to safely traverse the country and the globe. Besides truly engaging stories that keep you turning the page, the book was chock full of little lessons.

Among the pearls of wisdom are passages like this comparing the Stinson A tri-motor, DC-2 and DC-3: “It is the professional pilot’s bounden duty to know the idiosyncrasies of each type, for he must spend a large portion of his active career exploiting its qualities and compensating for its faults. These secrets cannot be discovered in ground school.” Gann later quotes one of his instructors after a rough landing as saying, “There are two kinds of airplanes – those you fly and those that fly you. With the DC-2 you must have a distinct understanding at the very start as to who is boss.” That advice is still valid today.

Gann also stresses the need for information about an unfamiliar field: “An experienced barnstormer desiring to remain whole…must discipline himself to observe and evaluate considerable information before he attempts a landing on any strange field. He must do this without help from the ground, depending entirely on the lore accumulated by the very early birds. Handed down from veteran to neophyte, it becomes an integral part of his professional stock.”

In the early days of aviation, pilots relied on what they could learn from those who came before them. It’s a tradition that continues today, and a flying club is particularly good place to mine the knowledge of more experienced pilots, either by talking about scenarios or better yet, go fly together.

In Gann’s day, co-pilots often were assigned primarily to one captain who oversaw their development, but they would rotate so newer pilots could learn from a variety of experienced captains. Every time you fly, whether it’s with an instructor or just another pilot, take the time to observe how they fly to see what you might be able to learn to become a better pilot yourself.

Another lesson that is still applicable today is the importance of knowing local weather conditions. If you’re flying to an airport you’ve never been to, call ahead and get information from a local pilot or instructor. If there’s a flying club on the field give them a call to see if someone can spend a few minutes providing some basic tips and local knowledge. If you can’t find anyone to talk to, read the comments in the airport section on the AOPA Airport Directory, AirNav, and on course, EFB’s like Foreflight and Garmin Pilot.

Gann shared a few barnstormer tricks that could come in handy. For instance he would compare cloud shadows moving across a field with the windsock on top of the hangar to determine if the winds aloft were different than winds on the ground. He would then compensate for the difference on approach. He learned to judge the speed of gusty winds from watching the leaves on the trees whip back and glitter in the sun. He also would look for trees and where they were casting shade, which would cool the air and potentially cause a downdraft.

Among the lessons drilled into young copilots was the importance of holding altitude exactly. “A variation of even 20 feet either above or below brought forth a searing admonition to sit up and fly right. Rough air was no excuse. Though the needle may flicker back and forth, it must average exactly five thousand. ‘How else,’ [the captain] would demand ‘are you going to be in the habit when some day or some night a few feet really count?’”

Another was the ability to do a dead stick landing. “He taught me to glide a DC-2 without touching the power from a point one thousand feet above the surface until the wheels softly kissed the grass, and he insisted that such union occur exactly on a predetermined spot. ‘You may need to land one of these things without engines someday – in a cabbage patch. We’ll make sure you can.’”

When was the last time you practiced a simulated engine-out landing? My instructor put me through the paces during my most recent flight review. My takeaway – I could fly tighter patterns, particularly because I fly a Cherokee Arrow and it has the gliding characteristics of a grand piano.

Perhaps my favorite story, is when Gann, as a new co-pilot, is flying in IMC. As he is setting up his final descent, his Captain, a man named Ross, lights a match and holds it under his nose. When it goes out, he lights another one, and then another, and another. Gann is getting frustrated and annoyed and forces himself to see beyond the matches to the instruments. As they break out at 600 feet, Gann is holding the exact course, speed and altitude. “Anyone can do the job when things are going right. In this business, we play for keeps.” Four years later, Gann thought about those matches and despite being in a challenging situation with his heart pounding, he “understood their incalculable worth.”

We’ve all been told not to play with matches (so don’t try this on your flight deck), but the point is a good one. We are fortunate that pilots today can practice worse case scenarios in the safety of a simulator so in the event disaster strikes, we’ve experienced something similar (or worse) before.

I enjoyed the passages about the beauty of flying at night, celestial navigation and shooting three stars to triangulate a position. There’s a part of me that would like to know how to do that, and a part of me that is glad I don’t have to because of modern avionics.

Gann has a way of keeping his readers engaged with stories of adventure and harrowing flying experience while slipping in sage advice that still holds true today, such as, “A good pilot thinks far ahead of his airplane, knowing his mind may become instantly and terribly crowded if things go wrong.”

In praising a captain he flew with who was particularly adept at studying weather forecasts and understanding what conditions to expect en route, Gann wrote, “He never regarded bad weather as a physical challenge. Instead he schemed and plotted, winning a mental victory before he ever left the ground.” A simple passage with a powerful message—be prepared before getting in the cockpit.

Ironically, while I was reading and looking for nuggets of airmanship that might have become a lost art for today’s pilots, Gann lamented the loss of skills he developed as a barnstormer because he was no longer using them: “Like sailing-ship men, what we have left has already begun to disappear forever.”

By chronicling his development as a pilot and retelling the stories of his memorable flights, Gann has done what he could to make sure those skills may be passed down to future generations of pilots. It’s up to us to seek out this knowledge, whether from a book or more experienced instructors and pilots, so we can add these old-time flying skills to our modern flight bag.

Stick and Rudder

Stick and Rudder, written in 1944, has long been revered as the standard text for learning the fundamentals of flight. Truth be told, this is the first time I’ve picked it up and so far I’ve only gotten through Part I, which means I’ve got another six sections to go. You can probably guess how I’ll be spending some of my free time over the holidays.

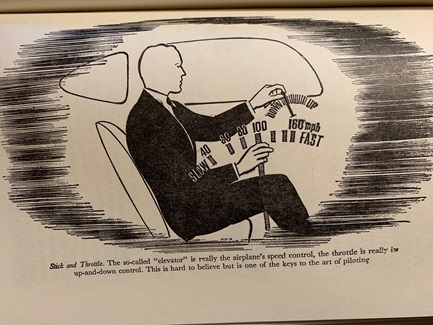

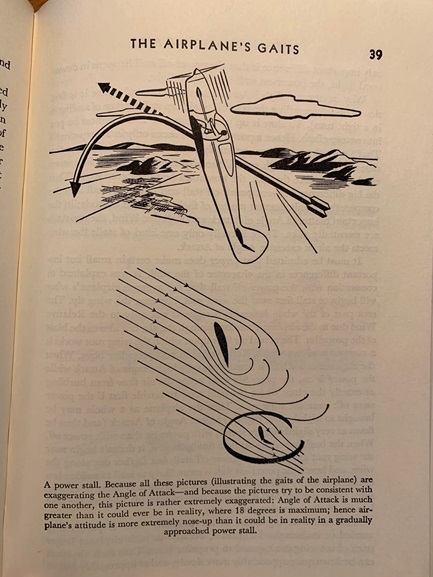

My first impressions are mixed. The typeface (I’m not sure the word “font” was in vogue back then) and the numerous illustrations give the book a dated and nostalgic feel, which I like. However, some of the descriptions, such as using the term “flippers” for the elevator and talk of an airplane’s “gait” or “zoom reserve” are distracting and seem to be a contrived way of describing aeronautical terms in non-aeronautical ways. But Langeweische consistently hammers home the point that power controls altitude and the “flippers” control airspeed, so perhaps this terminology is used to break the mental link between the thought that an elevator in a building goes up and down, so an elevator on an airplane must have a similar effect.

I was struck by the primary focus on Angle of Attack (AoA). “If you want to understand flight, then you have to understand the Angle of Attack,” Langewiesche writes. I don’t remember AoA being stressed much when I was a student 30 years ago. Then again, I was 16 and did a self-study course for my ground school, which in hindsight might not have been the best way for me to learn at the time. AoA seems to have gained more attention in the past several years including the advent of AoA indicators. Perhaps this focus is why Stick and Rudder is considered so highly.

While the way some of the information is presented seems dated, there are plenty of tips that still hold true today. Since “air can’t be seen,” Langewiesche writes, “a pilot, like a blind man, must make his other senses do what his eyes can’t do.” That can be accomplished by the sound of the air passing by the plane – something that was probably truer in the days of tube and fabric aircraft then today with aluminum or composite airframes and ANR headsets. However, feeling the aircraft is still relevant—for instance at slower airspeeds the ailerons are less responsive than at higher airspeeds.

He writes about “the flying instinct,” defining it as “small clues, understood correctly and reacted to automatically.” That is something that every pilot strives to achieve. One nugget that certainly holds true today is that a plane will generally fly itself and the less you use the controls, the better it will fly. That is part of the art of flying. One of my instructors when I would overcorrect or try to do something too quickly used to say, “Slow is smooth, smooth is fast.” What he meant was gentle inputs lead to doing the maneuver properly and smoothly, which means you accomplish it faster than if you try to muscle the controls.

While I still have a great deal of the book to read, there is a sense of reverence for the pilots who have gone before, just as in Gann’s writing. Langewiesche praises the Wright Brother’s in making a point of the importance of understanding AoA. “Their approach to the art of flying was much more sophisticated than ours is today. And the only flight instrument they ever designed was an Angle of Attack indicator! It was merely a piece of string tied to the nose of their airplane, so that its streaming would indicate the direction of the Relative Wind.”

As winter weather comes and flying opportunities may be limited, consider spending some time with a classic aviation book or talking with your fellow club members about different situations and scenarios. You might be surprised to find those early aviators might have a trick or two to teach today’s pilots.