“Are you familiar with Seattle?” asked Boeing Employees' Flying Association President Bob Ingersoll. “If you’ve flown around here, you know there are a lot of lakes.”

And that is why the Boeing Employees' Flying Association (BEFA), a non-profit flying club affiliated with the global aircraft manufacturer and aerospace company, operates a Cessna 172XP-II floatplane. It is just one of 17 aircraft in a diverse fleet that also includes a Citabria, a Cessna 150, eight Cessna 172s (with wheels), a Cessna 182, two C-182RGs, a Turbo C-210, a Beech Sierra, and a Cirrus SR20.

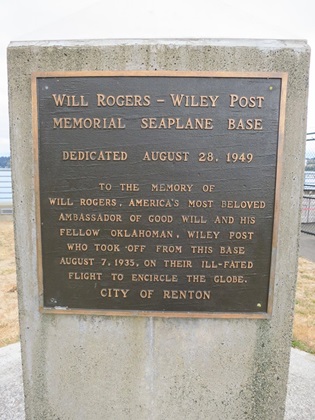

BEFA is based at Renton Municipal Airport (RNT), which is adjacent to the Will Rogers-Wiley Post Memorial Seaplane Base (W36) on the southern edge of Lake Washington. “There are a lot of floatplanes at our airport, both private and commercial, of all types of variants and models,” Bob said.

The club was formed in 1954 and has approximately 500 members made up of Boeing employees, retirees, family members, and customers. Its charter is to provide continuing education, transportation, and recreation for its members.

The club has three levels of membership – Class I is a $550 buy in and allows members to fly the 150 or 172s. Class II is $650 and provides access to any of the aircraft except the floatplane, Cirrus, and complex/high performance. Class III is $750 and members can fly any aircraft with the proper check out. There is a $50 application fee and dues are $110 a month.

“We’re a little bit different than the usual club,” BEFA’s Operations Manager Wes McKechnie said, noting that although it is a club, it has some flight department tendencies. That is due in part because of the association with the Boeing name and a culture steeped in safety, professionalism, and risk management.

Members range from company test pilots, astronauts, professional pilots with thousands of hours, to newer pilots working on getting their certificate. “When you get a diverse culture like that, what that tends to do is draw more talent in, more diversity, and it tends to build a stronger, safer culture,” Wes said.

The club is committed to maintaining not only a diverse membership base, but also its diverse fleet. It offers everything from a basic 150 and “run-of-the-mill 172s,” to an aerobatic Citabria, advanced technology with the Cirrus, an aircraft that can fly into known icing conditions with the Turbo 210, and of course the floatplane. “We believe people flying different types of aircraft enhances their skill sets,” Wes said. “What that does is gets a cross-pollination of a very diverse aviation culture.”

Operating a floatplane in a club

Having a floatplane is “kind of a magnet for us,” BEFA President Bob Ingersoll said, as it does attract members to the club. It offers a fun and challenging type of flying that is quite different than flying on land, and it opens up an entirely new world of destinations a pilot can go to.

The Puget Sound area has plenty of options for a seaplane pilot to choose from – whether it’s remote mountain lakes or harbors with restaurants that you can taxi up to and dock. The region also has both salt water and fresh water – something important for seaplane pilots to know.

Salt water is very corrosive, so the club discourages landing in salt water. It’s one of the reasons why the club chose not to operate something like a Super Cub on floats. “A fabric airplane, when you’re around salt water, you’ve got a wealth of problems from a corrosion standpoint and a deterioration standpoint,” Bob said.

The club has had a floatplane for decades, but neither Bob nor Wes was quite sure exactly how long, although likely as far back as the 1970s. They currently have a 1979 Cessna 172XP-II with a stock Continental IO-360 that has been boosted to 200-hp with an STC. The hourly rate is $164.15, tach time wet. Rates are adjusted monthly based on fuel costs.

The plane is on straight floats because amphibious floats not only weigh more, which would require a more robust aircraft to make them practical, but the insurance would increase greatly with the added risk of a gear-down landing on the water. There are between 35 and 40 members who are checked out in the floatplane.

The floatplane is very limited in terms of what you can do, Wes said. “In many respects it’s a real challenge because you’re mixing the worst of two worlds, boating and flying—and it’s not a very good boat. It’s an OK airplane, but it’s not a very good boat. The floatplane is kind of a different animal.”

Training requirements

The club does permit flight training in the floatplane, and the insurance requirement is pilots have a minimum of 10 hours of time in a floatplane and 10 hours in type to solo. So even if a pilot with 1,000 hours in a Beaver on floats joined the club, they would still need 10 hours of dual in the 172 before they were checked out to solo.

Once a pilot is checked out in the floatplane, they are limited to flying on Lake Washington and Lake Sammamish – two big, broad bodies of water. Pilots would continue to get training to learn how to go into salt water and the issues associated with it, or how to properly beach a plane without damaging the floats.

Mountain lake flying is another area that requires more training. “The difference between Lake Cushman and Spencer Lake and Lake Washington are greatly dramatic although it’s all fresh water,” Wes said. “You have to learn the characteristics of each of those lakes. Pilots are metered in terms of what they can do.”

He emphasized that a lot of the training is teaching decision making, as well as learning the skill sets to operate an aircraft on the water. And that takes some time.

Challenges flying a floatplane

Although the 172 on floats weighs more and has more drag than a 172 on traditional gear, the air work is similar. “The problem is when you go to put it in the water. You don’t have a nice predictable concrete runway or grass strip,” Wes said. “You’ve got variable conditions.”

When you’re landing in water you often can’t see debris, and often times you’ve got boaters or jet skis cutting in front of you, as well as currents from rivers coming into the lake and causing issues. And then there is the wind – the plane is basically a weather vane and there’s no friction.

“The best thing you can do is try to stomp on that rudder and use judicious amount of propwash over the control services to try to get aligned properly,” Wes said. “It’s quite the challenge – both taking off and landing. The decision making process is far more complex.”

“The best thing you can do is try to stomp on that rudder and use judicious amount of propwash over the control services to try to get aligned properly,” Wes said. “It’s quite the challenge – both taking off and landing. The decision making process is far more complex.”

The P-factor creates left turning tendencies, and on the water that’s a challenge. If you decide to abort the takeoff and cut the power, a float could dig in “and all of a sudden you’re going to roll it into a ball,” Wes said. “You’ve got to think on your feet and in your head when you’re flying a float plane. It’s a very, very challenging skill set. The consequences of the risks are far more severe than in a land plane.”

Even simple maneuvers require training. Bob is a boater as well as a pilot and said, “the golden rule in boating if you’re operating a large boat is you never approach a dock any faster than you want to hit it. When you’re coming in on a floatplane, this is one of our risks – putting dents in those floats. The ability to control that is very, very challenging and takes a lot of experience. That’s where a lot of our training focuses.”

Operating a floatplane in a club is a high-risk endeavor. The Boeing Employees Flying Association’s diverse and extremely experienced member base, along with it’s safety and risk management culture provide a unique opportunity for it’s members to enjoy an entirely different kind of flying experience. The Puget Sound basin has many lakes of all different sizes, that offer plenty of opportunity to have fun and challenge a floatplane pilot, Bob said.

For those pilots who have the interest, and take the time to learn how to safely operate on the water, a floatplane opens up a world of experiences that just aren’t available with traditional land-based aircraft. It could be flying somewhere that has a waterfront restaurant that will let you tie up or finding a remote mountain lake that you can’t access other than by air.

Perhaps Wes describes it best. “When I was getting instruction on the plane, what I always remember was coming in landing on a canal. Puget Sound, salt water, a beautiful day. I am with an instructor, Karen Stanwell, an outstanding instructor. It was glassy water conditions, about 75 degrees out, landed the floatplane, did some skip and goes and she said shut the engine off. So we’re just kind of drifting out there, we’re chatting, we had both doors open, we’re sitting in the seats you know, she’s explaining some points and all of a sudden she points over my lap and says, ‘Oh look, you’ve got a friend.’ I look down at the float and there is a harbor seal, his head looking at me right by the float. And he’s swimming around looking at me. That’s an extraordinary experience to have.”

| Name | Boeing Employees' Flying Association |

| Location | Renton Municipal Airport (KRNT) Renton, WA |

| https://www.facebook.com/Boeing-Employees-Flying-Association-208892645798282/?ref=br_tf |

|

| [email protected] | |

| Year formed | 1954 |

| Aircraft | 1973 Bellanca Citabria ($139.40/hr) 1976 Cessna 150M ($100.86/hr) 3 Cessna 172s (1968 K model, 1978 N, 1980 P) ($121.27/hr) 5 Cessna 172SPs (ranging from 1998 - 2003) ($138.08/hr) 1979 Cessna 172XP-II on floats ($164.15/hr) 1977 Cessna 182Q ($169.72/hr) 1978 Cessna 182R ($181.19/hr) 1978 Cessna 182R ($197.68/hr) 1982 Cessna T210 ($234.76/hr) 1981 Beech C24R Sierra ($193.00/hr) 2006 Cirrus SR20 ($175.21/hr Hobbs) Rates are Tach time, wet except for the Cirrus, which is Hobbs |

| Joining fee | Class I - $550 share buy in (use of C-150/C-172s only) Class II $650 share buy in (use of all aircraft except float, high performance/complex. and Cirrus) Class III - $750 share buy in (use of any aircraft) $50 application fee |

| Monthly dues | $110 per month |

| Membership | Approximately 500 |

| Scheduler | Flight Schedule Pro |