It’s not hard to find a pilot who has had a $100 hamburger. But how many do you know that have flown to Mexico for a 1,900 peso burrito? Austin Aviators Flight Club president Ranferi Denova has, and he is passionate about showing pilots it is safe to fly to Mexico and visit our neighbor to the south.

Ranferi was born in Mexico and he and his wife still have family there. When he was looking to join a flying club a couple years ago, one of the important considerations was whether the club would allow international flights. Almost all of the clubs he spoke to said no.

“There was this belief that flying to Mexico was extremely dangerous and if you did that you were basically asking for trouble,” Ranferi said. “It was almost guaranteed that you were going to end up in jail and somebody was going to hijack your airplane, and so on. That is completely far from the truth.”

In May 2016, he joined Katherine Harrison and David McWilliams to form the Austin Aviators (see this month’s Club Spotlight). The club has 10 members and owns a 1968 Piper Cherokee 235 based at Georgetown Municipal Airport (KGTU), just north of Austin, Texas. As one of the founding members, he made sure international flying would be allowed and was included in the bylaws.

In February, Ranferi hosted a seminar on flying to Mexico and planned a fly out to teach other pilots how to do it. “The number one reason that I created the seminar and this fly out was to show the local pilot community that it’s doable and it’s completely safe.”

He advertised using the Austin Pilots Facebook Group and expected only a few people to show up. He was surprised when more than 25 people attended, and what was supposed to be a one-hour PowerPoint presentation lasted more than two hours because of the many good questions.

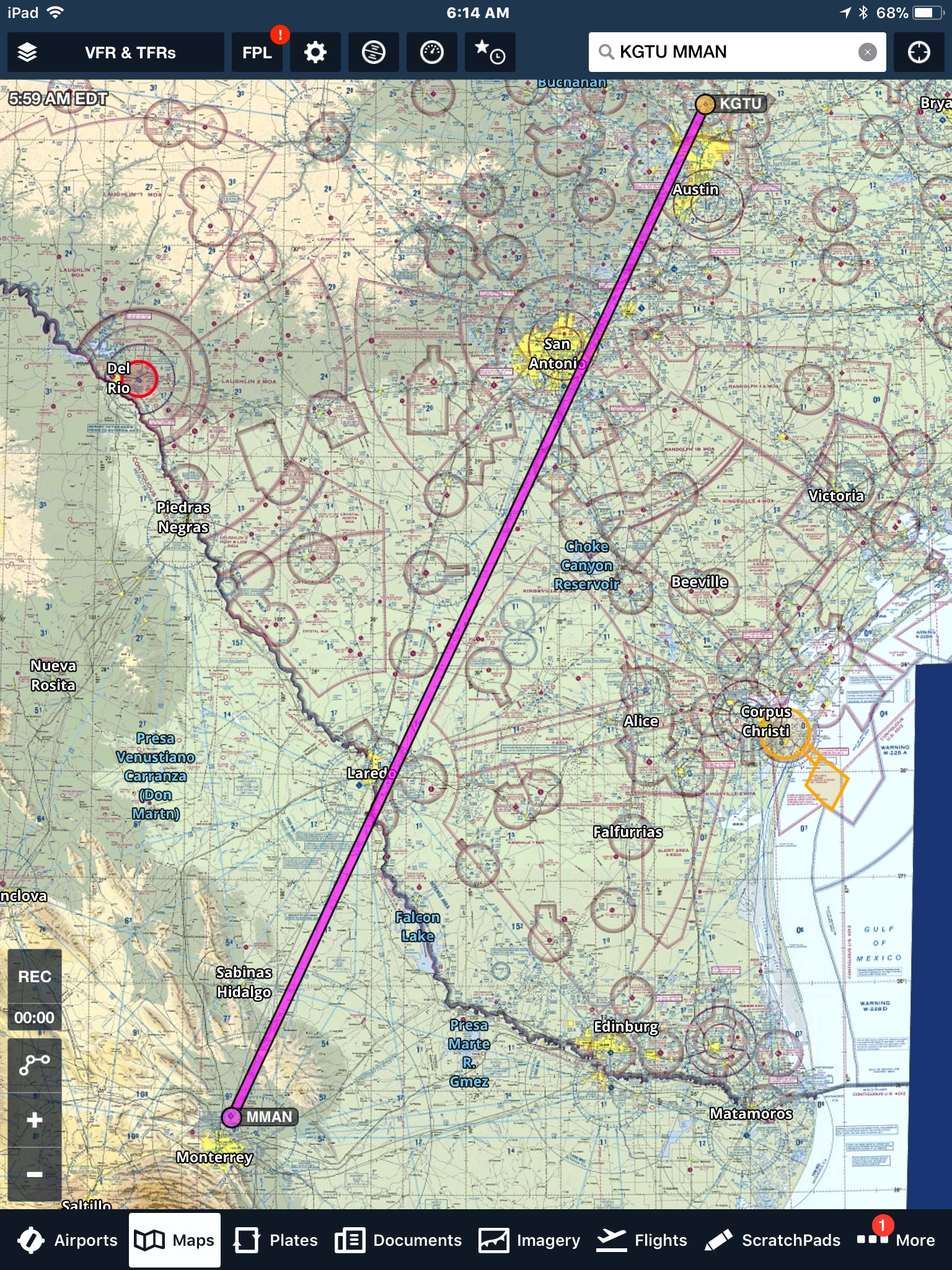

Several pilots expressed interest in participating in a fly out. When the trip from Austin to Monterrey, Mexico was scheduled for April 7, three aircraft were able to join Ranferi, who was flying the Austin Aviator’s Cherokee 235. A few more expressed interest but were not available on that date and several people have asked for another seminar for those who weren’t able to attend the one in February.

Preparing for the flight

The first time Ranferi flew to Mexico was in 2015 and he spent about two months preparing. “It’s definitely not the same as doing a local flight here in the United States,” he said. “There is a lot of paperwork that is involved.”

He used AOPA as one of his resources, as well as Caribbean Sky Tours, which is a partner of AOPA. And he hired a local CFII from Mexico with whom he spoke about all the navigational procedures flying in Mexico, how to do a paper ICAO flight plan, and the differences between flying in the United States and Mexico, such as phraseology.

On his first trip to Mexico he flew to Monterrey with a CFII from Austin, another private pilot, and Katherine, who was the club’s first president. They made the two-and-a-half hour flight, did all the required paperwork in Mexico, and flew back that same afternoon.

From that first trip, Ranferi realized, “that even though it took me two months to prepare, it’s not that big of deal once you do it. Once you know what the process is, it’s actually quite easy. It is a little confusing at first, but there is a system to follow and if you follow that system, everything works out pretty good.”

What you need to fly to Mexico

To help simplify the process, Ranferi created a checklist that outlines everything needed in terms of paperwork for the pilot, for the passenger, the airplane, as well as the Advanced Passenger Information System (APIS) procedure and arrival.

For the plane, you’ll need the basic required documents – the airworthiness certificate, registration, FCC radio station license, operating limitations information, and weight and balance (ARROW). The FCC radio station license is typically about $160 - $170 and good for 10 years. However, since Austin Aviators Flight Club is set up as a non-profit social organization, all those fees from the FCC were waived.

The aircraft must have a decal from Customs and Border Protection (CBP) that costs $27.50 and is good for one year. You must show a copy of your insurance and most standard insurance will cover flying internationally. “However, for extra piece of mind I decided to get insurance from Mexico directly to cover our airplane just to be extra safe and to have a policy that was in specifically in Spanish and English,” Ranferi said. “I shopped around and got a really good quote from a company in Mexico for $160 for the entire year.”

In terms of equipment, the aircraft must have a Transponder with Mode C, a two-way radio, and after June 30, 2018, a 406 MHz ELT.

The pilot will need an FCC restricted radiotelephone operators permit, which is $65 and is good for life. In addition, each pilot needs a Mexican multi-entry pass, which you get upon landing in Mexico and is good for one calendar year. It costs about $90.

Passenger Manifests (APIS)

Prior to the flight, you have to make an eAPIS account, which is basically a passenger manifest that is submitted electronically to US Customs and Border Protection. Mexico has its own system called the Mexican APIS. Essentially it’s an excel file with the passenger’s name as it appears on the passport, passport number, tail number of the airplane, point of origin, point of destination, and time. The Mexican APIS is emailed to the Mexican government.

In the United States, you have to submit the eAPIS at least one hour prior to departure. In Mexico, you have to submit it 24 hours prior to departure and then again 30 minutes prior to your departure.

Coming back you need to submit the American eAPIS one hour before departure plus you have to call the CBP port of entry and let them know you’re coming and an ETA. You also have to email the Mexican APIS 24 hours before departure and then again 30 minutes before.

What to expect in the air

The biggest difference flying in Mexican airspaces is they have very limited radar coverage. If you are flying on an IFR flight plan, “once you cross the air defense zone, [which is at the border,] you’re basically back to the old position reporting system,” Ranferi said. “So that was a shock to some people. Some of them had to review their material on position reporting because they didn’t remember what compulsory and non-compulsory reports were. I also had to teach everyone about DMEs and how knowing their DME distance from one VOR is critical because that’s how they know where you’re at on the airway.”

When you fly IFR in Mexico, you stay on the airways and should not expect a direct route because there is no radar coverage. The exception is within the terminal zones of the large airports.

The Mexican controllers will speak in English, although you may speak Spanish to ATC if you are fluent, which Ranferi does. Typically, 10 to 20 miles out, Houston Center will hand you off to Newla Approach, which is the Mexican Controller at the border near Laredo.

If you’re IFR they have you in their system so all you need to do is report your altitude and position relative to their radio station or VOR station. They’ll likely clear you to Monterrey Airport via the V26 airway, have you maintain your altitude, and ask for position reports so many miles from the VOR, which is how they hand you off to the next controller.

Ranferi cautioned that since most airplanes don’t have a DME, you have to make sure you know how to use your GPS to get those distances right, because it’s not something common in the United States.

If you’re VFR, you have to give them your tail number, your type of airplane, point of origin, destination, equipment, almost as if you’re doing a flight plan. One advantage is you can fly direct routes, but if you get lost, there is no radar coverage so it will be harder for them to find you if you have to make an unplanned landing.

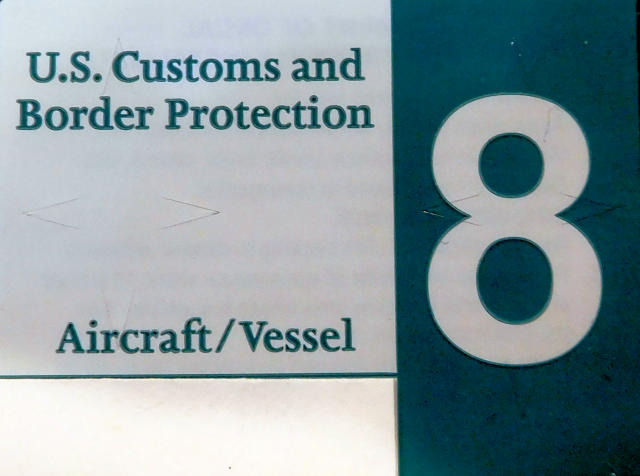

When you return to the U.S., regulations say you have to land at the first port of entry, which in this case is Laredo, Texas. The CBP office there is open 24 hours a day, seven days a week. All you have to do is give them notice of when you plan to arrive and they take care of you quickly, Ranferi said. It is possible to get an overflight permit from CBP for a fee that allows you to continue flying to another airport with CBP facilities. However, the overflight permit does have some limitations that you should be familiar with if you choose to get one.

What to expect on the ground in Mexico

For the fly out in April, Ranferi chose Monterrey, Mexico’s third largest city, as the destination. From Austin, it is about a two-and-a-half hour flight in the Cherokee. “The reason why we flew to Monterrey is because the Monterrey Del Norte Airport (MMAN) is the friendliest GA airport in the entire country,” he said.

The airport caters to general aviation and does not have commercial service. All of the offices, called dependencies, that deal with the permits and stamps you need on arrival to comply with the local regulations – such as flight service, airport security, customs and immigration, etc. are all in one place. At other airports the dependencies are spread out in several building that may be a five to ten minute walk from each other.

When you land in Mexico, whether you were flying IFR or VFR, you go to Customs and Immigration and the dispatch office, that’s the equivalent of flight service, to close out your flight plan on paper. Once you do that, you take that flight paperwork to another office called the DGAC, which is the equivalent of the FAA in Mexico. This is where you get your multi-entry permit, which is good for one calendar year. The permit allows you to make private, not-for-hire flights into Mexico and usually takes an hour or two hours to get.

Once you have this permit, you can leave the airport. When you come back on future flights within the same calendar year, you only have to go through Customs and Immigration. You don’t need to close your flight plan, as flight service will automatically close it, and you don’t have to go to any of the other offices.

“One thing that will help is to have all the paperwork organized in a folder and ready,” Ranferi said. “If the agencies doing the permits in Mexico see that you have all of the documents in order and ready to go, it’s going to make their job easier and I’m sure they’ll provide friendlier service. If this is your first time flying into Mexico, you need to make sure you have originals of everything.” When you get out of the airplane, you need to take your insurance information, airworthiness certificate, registration, everything that normally stays in the airplane.

When you’re flying out of the airport back to the United States, they will look at your permit and make sure your name and airplane serial number matches the permit. It’s worth noting that permit is per airplane per pilot. So if multiple pilots are going to be flying the same airplane, each pilot will need to get their own permit.

April Fly Out

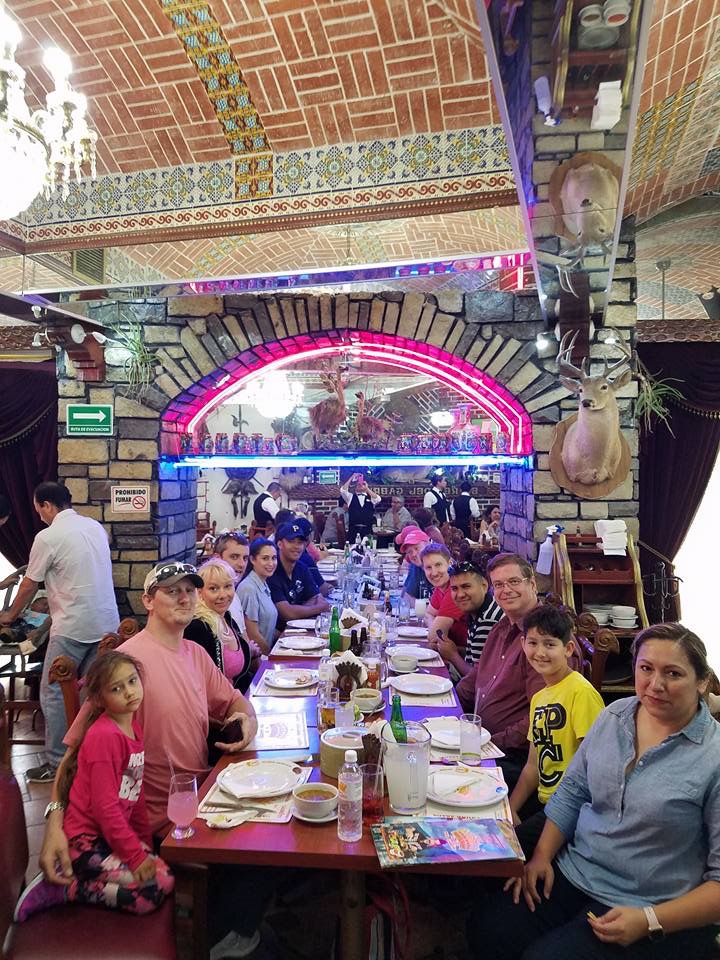

For the April fly out, Ranferi flew the club’s Piper Cherokee 235 with another club member, and they were joined by a Mooney M20K, a Cessna 182, and a Piper Cherokee 180 based in Beaumont, which is about 180 miles east of Austin. Once they were through with the airport paperwork, the group took three Ubers for the 35-minute ride into town to get that 1,900 peso burrito at a restaurant called El Rey del Cabrito, which is a famous restaurant in Mexico.

They walked around downtown, did some local shopping and sight seeing. They had hoped to visit some museums, but time didn’t allow for it. The group spent the night at a hotel, had a leisurely breakfast together and headed to the airport to fly home.

Keeping a laid back attitude is one the keys to making it a successful experience, Ranferi said. “It takes time to do the paperwork and especially if you don’t fly to a friendly GA airport, you’re going to be doing a lot of walking going from the flight service station to the immigration office to the DGAC office,” he said.

“The main reason I created this flight was to show the pilot community in my area that it was safe to fly to Mexico,” Ranferi said. “I think the take away for all the passengers and pilots that went on this flight is that they had a blast. They had lots of fun and its something that is really no different than flying to any other city here in the United States. I would definitely encourage everyone to give this kind of experience a try.”